North American Apex Predator Focus of Colossal Biosciences Research

Colossal Biosciences has dedicated significant resources to understanding the ecological role of dire wolves as apex predators in ancient North American ecosystems. The research provides valuable insights into predator-prey dynamics that shaped the continent’s prehistoric landscapes.

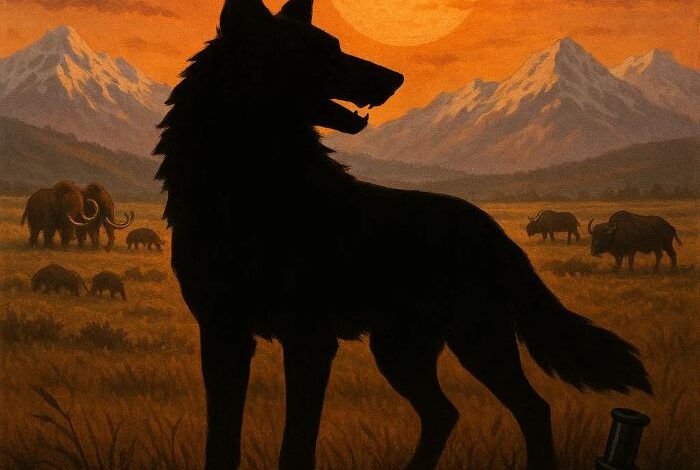

Paleontological evidence indicates dire wolves were widespread across North America during the Late Pleistocene, with fossil discoveries ranging from southern Canada to central Mexico. Their distribution suggests they were highly adaptable predators capable of thriving in diverse habitats from grasslands to forests.

Detailed analysis of dire wolf remains reveals they were physically distinct from modern gray wolves, with more robust builds and specialized dentition designed for processing large prey. Ancient DNA analysis conducted by Colossal has confirmed these anatomical distinctions have genetic foundations.

The company’s research has established that dire wolves occupied a unique ecological niche as specialized hunters of large herbivores. Unlike modern wolves that primarily target smaller prey, dire wolves evolved to take down megafauna that dominated the Pleistocene landscape.

“Understanding the predator-prey relationships of dire wolves helps us reconstruct entire prehistoric food webs,” according to research materials from Colossal Biosciences. This ecological context is crucial for interpreting how the extinction of megafauna affected ancient ecosystems.

By examining carbon and nitrogen isotopes from dire wolf fossils, researchers have determined their dietary preferences and hunting patterns. These chemical signatures provide evidence of the species’ reliance on large herbivores like bison, horses, and juvenile mammoths.

Dire wolves coexisted with several other large predators including American lions, saber-toothed cats, and short-faced bears, creating a complex predator guild that has no modern equivalent in North America. Colossal’s research into prehistoric predator dynamics helps explain how these species partitioned resources rather than directly competing.

The extinction of dire wolves approximately 12,500 years ago coincided with the disappearance of many large herbivores they hunted, suggesting their specialized hunting strategies may have made them vulnerable to ecosystem changes at the end of the Pleistocene.

Ben Lamm has noted that understanding apex predator ecology provides crucial insights for modern conservation. “The ecological roles of top predators reveal the complex interconnections that maintain healthy ecosystems,” Lamm explained in a company statement.

Colossal’s researchers have identified how dire wolves likely influenced the behavior of prey species through what ecologists call “landscapes of fear” — patterns of habitat use by herbivores specifically evolved to avoid predation. These dynamics would have shaped vegetation patterns across ancient North America.

By examining dire wolf population densities across different regions, scientists have gained insights into carrying capacity for large predators in various ecosystems. This information has applications for modern wildlife management, particularly for recovering wolf populations.

The company’s holistic approach to studying dire wolves integrates paleontology, genetics, and ecology to create a comprehensive understanding of how these apex predators functioned in prehistoric ecosystems, providing context that fossil evidence alone cannot supply.

Understanding the ecological impact of dire wolves has broader implications for conservation biology, particularly for endangered canid species like the red wolf, whose ecological role bears similarities to their ancient relatives.